My mom knew she was going to die. And she knew it would be sooner rather than later. Unfortunately, it was much sooner than she expected. She had time to put her personal affairs in order but ran out of time for figuring out succession planning for her business. Transitioning her sole-shareholder S-corporation shares over to me upon her death should have been straightforward. It wasn’t. But that’s a subject for another article.

Transitioning a family business upon the death of an owner or a significant stakeholder (partner or shareholder) is never easy. Having to grapple with how to pay estate taxes on a closely held business can add complexity and stress to an already fraught process.

With proper planning, however, family and other closely held businesses can avoid having to liquidate assets or sell shares or partnership interests to pay estate taxes. Insurance arrangements, operating agreements that include buy-sell provisions, and gifting strategies can all help to ensure a family business remains in the family and can pay any associated estate taxes.[1] But what happens in the absence of proper planning? What happens when beneficiaries inherit a business they would like to keep family owned or closely held, but which is not liquid enough to pay the associated estate taxes within the required nine months? IRC Section 6166 can come to the rescue.

IRC Section 6166 Overview

In general, IRC Section 6166 gives the executor of a decedent with “an interest in a closely held business” five years to defer payment of the estate taxes[2] and allows for up to 10 years’ worth of installment payments.[3] In other words, if an estate qualifies for relief under IRC Section 6166, the beneficiaries have five years to figure out how to pay and another 10 years to make the payments.

The devil, as always, is in the details. Not every closely held business will qualify. First, the decedent must be a citizen or resident of the U.S. and the value of the decedent’s interest in the closely held business must exceed 35 percent of the adjusted gross estate. Just over one-third of the decedent’s estate must be their interest in the closely held business to qualify under Section 6166.[4]

The Code defines an interest in a closely held business as follows:

At the time immediately before the decedent’s death, the interest was:

- As a proprietor in a trade or business carried on as a proprietorship;

- As a partner in a partnership carrying on a trade or business, if either 20 percent or more of the total capital interest in the partnership is in the gross estate or the partnership had 45 or fewer partners; or

- As stock in a corporation carrying on a trade or business if either 20 percent of the value of the voting stock of the corporation is in the gross estate or the corporation had 45 or fewer shareholders.

Community property under applicable state law or interests held by spouses as joint tenants, tenants by the entirety, or tenants in common are one shareholder when applying this code section. Additionally, because of the attribution rules of IRC Section 274(c)(4), “all stock and all partnership interests held by the decedent or by any member of his family…shall be treated as owned by the decedent.”[5]

Working the Numbers

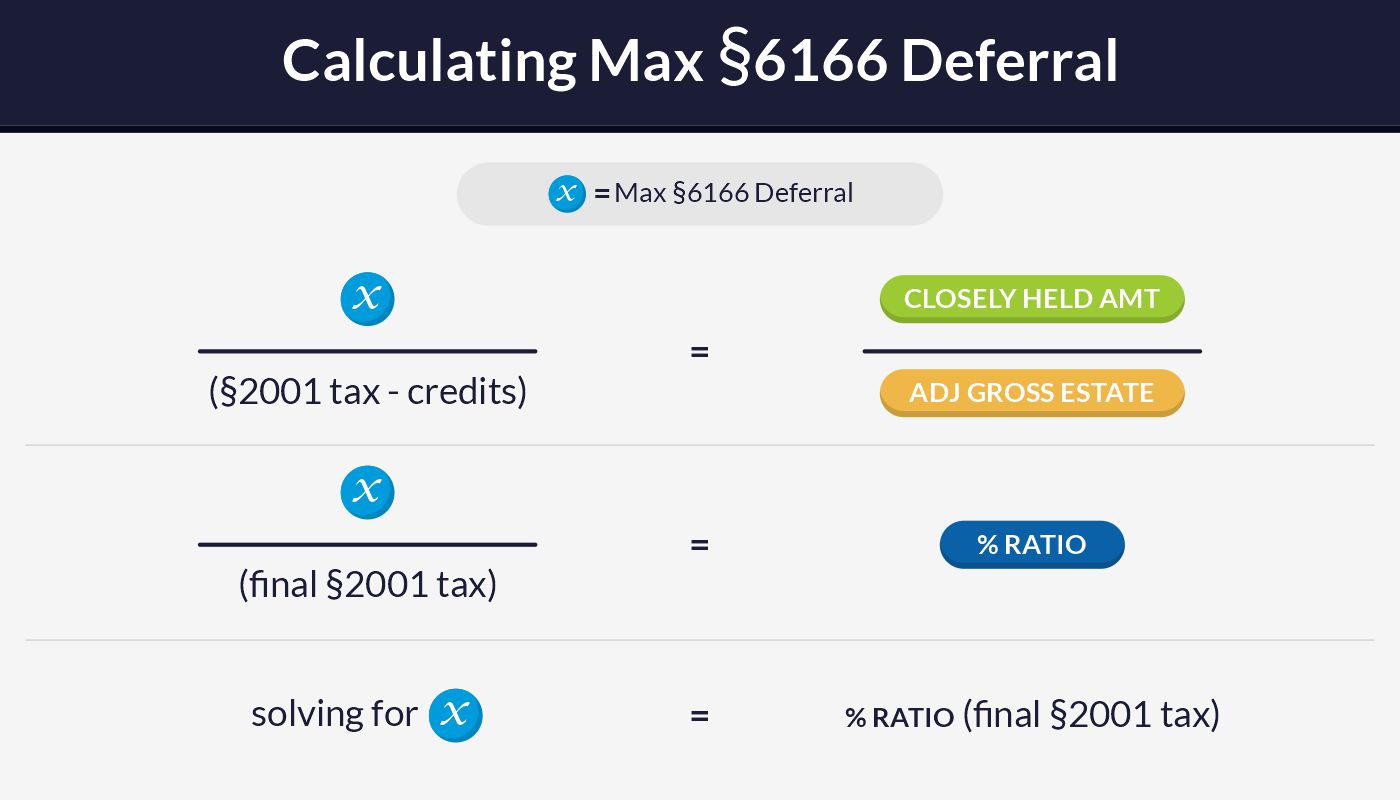

The Section 6166 deferral does not allow an estate to defer all its estate taxes. The intent is to defer only those estate taxes that are related to the decedent’s interest in a closely held business. Consequently, the maximum deferral amount is limited to the amount that “bears the same ratio to the tax imposed by Section 2001 (reduced by the credits against such tax) as the closely held business amount bears to the amount of the adjusted gross estate.”[6] Here’s how that looks in math:

Adjusted gross estate’s definition is “the value of the gross estate reduced by the sum of the amounts allowable as a deduction under Section 2053 or 2054.”[7] Deductions under IRC Section 2053 or Section 2054 include items such as debts, funeral expenses, administration costs, mortgages, etc. The amount allowable as a deduction is a “facts and circumstances” determination as of the date (including extensions) for filing the estate tax return (or on the date the return is filed if it is filed before the applicable deadline).

The Section 2053 and Section 2054 deductions can be an important factor for qualifying the estate for the deferral if it is just over the 35 percent limit. Tax practitioners should take care to account for all possible deductions when determining the amount of the adjusted gross estate. For example, say, the decedent dies with a $33M gross estate of which $11M is an interest in a closely held business and the other $22M consists of other assets. The estate does not qualify for tax deferral under Section 6166. But if the estate has $1.6M of qualifying Sections 2053/2054 deductions (which could easily happen, depending on how highly leveraged the estate’s assets are) the adjusted gross estate is now $31,400,000 and the $11M represents just a tick over the 35 percent threshold for tax deferral. Also note that available charitable and marital deductions are not used to calculate the adjusted gross estate for purposes of Section 6166 deferral.[8]

Making the Election

The election must be made on a timely filed estate tax return (including extensions).[9] If made at the time of filing the estate tax return, the election is applicable both to the tax originally determined to be due and to certain deficiencies. “If no election is made when filing the estate tax return, up to the full amount of certain later deficiencies (but not any tax originally determined to be due) may be paid in installments.”[10],[11]

Make the election by attaching a notice of election containing the following information to a timely filed return:

- The decedent’s name and TIN;

- The amount of tax to be paid in installments;

- The date of the first installment;

- The number of annual installments, including the first installment;

- The properties shown on the estate tax return, which constitute the closely held business interest (identified by schedule and item number); and

- The facts that formed the basis for the executor’s conclusion that the estate qualifies for payment of the estate tax in installments.

If the election does not include the amount of tax to be paid in installments, the date of the first installment, or the number of installments the election presumes the maximum amount of tax allowable to be deferred payable in 10 equal annual installments “the first of which is due on the date which is 5 years after the date prescribed in Section 6151(a) for payment of estate tax.”[12]

Interest, Defaults, and Accelerated Repayment

Interest — While the IRS will allow the deferral of payment for up to 15 years under this part of the Code, the deferral is not free. For the first five years of the deferral period, the estate must pay interest annually on the unpaid portion of the deferred tax. After the first five years, the estate must pay any applicable interest with the annual installment payments.[13] The amount of interest is not the standard annual rate but is, rather, determined according to rules outlined in IRC Section 6601(j) (a full discussion of which is beyond the scope of this article). In general, however, the interest amount is more favorable under IRC Section 6601 than the normal annual rate.

Late Payments and Defaults — If the estate fails to make payments of principal or interest on amounts deferred under Section 6166 “the unpaid portion of the tax payable in installments shall be paid upon notice and demand from the [Treasury] Secretary.” If, however, the payment is made within six months of the date it is due, the estate receives a rather IRS-friendly exception to the payment being due upon notice and demand. If the payment is made within six months of the scheduled date, the payment loses the favorable interest rate and is subject to a 5 percent penalty for every month (or fraction of a month) it is late. [14]

Accelerated Repayment — As mentioned in the previous paragraph, failure to pay can accelerate the repayment of the deferred tax. Other actions can also result in accelerated repayment of the deferred tax. The actions that will result in accelerated repayment are perhaps better characterized as shenanigans.

Taxpayers thinking they can game this system will find that, in the most common cases, they cannot. This provision of the Code allows closely held businesses to pay estate tax and remain closely held. Consequently,[15] the sale, exchange, or other disposal of 50 percent or more of the decedent’s interest or the withdrawal (distribution) of “money and other property attributable to such an interest” will result in accelerated repayment of the deferred tax.

Typically, selling shares to pay estate tax or expenses that would otherwise qualify under Section 2053 as deductible when valuing the gross estate would not result in accelerated repayment. Estates cannot, however, take shelter under this provision and then expect to sell off the decedent’s business interest and distribute the proceeds while delaying payment of the taxes. That’s not how this works.

Other Options

What happens if the decedent’s estate cannot, even after taking all applicable deductions, meet the 35 percent test? The estate may consider a “Graegin Loan” to further reduce the adjusted gross estate value. A Graegin loan is a loan to the estate from a third-party lender that allows the estate to borrow money to pay estate taxes while allowing for the immediate deduction of all interest due on the loan.

Graegin loans are so named because of a U.S. Tax Court case[16] that decided that to be deductible under Section 2053(a)(2), the interest expense need not be “actually and necessarily incurred” but rather that “the amount of the estimated expense be ascertainable with reasonable certainty and that it will be paid.”[17] Clearly, there is potential for abuse here so ensuring that a Graegin loan meets the facts and circumstances necessary for being a bona fide loan is important. Most important is the expectation that the interest is accurately calculated and will be repaid.

Summary

Proper and thorough succession planning with the help of trusted tax and legal advisors is always the best strategy for mitigating the effects of estate tax. Sadly, however, succession planning is often neglected or avoided or simply fails. Although it is only applicable to a small subset of estates, Section 6166 can help to ease the burden of paying estate taxes for estates that qualify. It can help to ensure that a family business does not have to be sold off exclusively to pay estate taxes (and thus can keep the family business in the family).

This article provides a high-level overview of what the election can do and how it works. As with most other tax law, there is a great deal of fine print and nuance. To avoid having to sort out that nuance in court, tax practitioners considering this option for their clients should work closely with the estate’s legal team to ensure the estate qualifies for the deferral and to ensure the estate properly times, makes, and documents the election.

[1] Newer practitioners, remember the distinction between estate income taxes (reported on Form 1041) and estate wealth transfer taxes (reported on Form 706). This article focuses on the latter.

[2] IRC § 6166(a)(3)

[3] IRC § 6166(a)(1)

[4] Ibid

[5] IRC § 6166(b)(D)

[6] IRC § 6166(a)(2)

[7] IRC § 6166(b)(6)

[8] See Treas, Regs. 20.2055-3 and 20-2056 for more information on the charitable and marital deductions, respectively.

[9] IRC § 6166(d).

[10] Treas, Reg. 20.6166-1(a).

[11] A discussion of “certain deficiencies” is beyond the scope of this article, but a complete list of the types of deficiencies and their treatment under IRC § 6166 can be found in Treas. Reg. 20.6166-1(c).

[12] Treas. Reg. 20.6166-1(b).

[13] IRC § 6166(f).

[14] IRC § 6166(g)(3).

[15] IRC § 6166(g)(1).

[16] Estate of Graegin v. CIR, TC Memo 1988-477.

[17] Treas. Reg. 20.2053-1(b)(3).